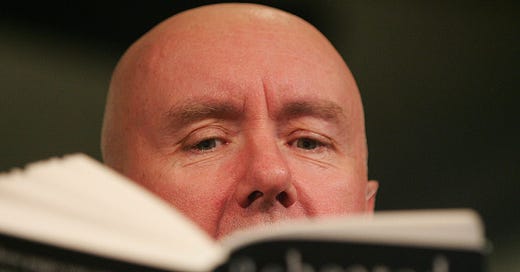

The following are a few quotes from Irvine Welsh. His landmark novel Trainspotting turns thirty years old, and he reflects on whether or not it could be launched these days.

To read the entire article, click here.

So how did Trainspotting come about?

Well, I was involved in house music in the late Eighties. There were a lot of interesting people living in Edinburgh at the time; people like Kevin Williamson, Barry Graham, Duncan McLean, Gordon Legge. They were all writing, but we didn’t really see it as a movement at the time. Kevin, Duncan, and Barry would put on different events—and I went to them. I found it quite interesting, and I thought it would be a nice thing for after raves, so people could relax and kinda come down. Just to have something that was a bit less… taxing. Open mic stuff and all that, you know?

My editor, Gerry Howard arranged a book tour for Welsh and many of the friends mentioned above. It was the golden age of “lad culture” and the group was to appear in cities across the United States, as the “Great Scots” tour. As per Gerry, the tour fell apart after a couple cities. It was too difficult to wrangle the hard-drinking writers and marshall them between airports, hotels, and venues.

What was the source of the novel?

I mean, I had all my—for want of a better term—heroin journals. I wanted to make a book out of them. Well, I wanted to write them up as a sort of journal first, but then I wasn’t really interested in my own voice. I was interested in the parts where I was an unreliable narrator; where I was being quite self-aggrandizing, exonerating myself from things, pointing the finger at other people. You know, classic deflection. Excuse and all that. When I veered into fiction, it was more interesting; but when I started to write in different voices, I found my own voice wasn’t enough to tell the story. So, I started to create different characters to tell these stories. It just grew out of that. I started to write these stories and feed them into magazines and journals: the small underground presses that were publishing at the time. Then, you know, when Robin Robertson got in touch, the editor at Random House, I kinda said to him I’ve got a book—I didn’t really have a book, I just had a collection of these stories—so, I basically went for it. He said he wanted to see it, so I wrote them up as a book. I didn’t really know how to write a book. I didn’t know how to… finish it. So, I just wrote a heist ending. To stop it, basically.

Interesting, the novel Fight Club also began as a collection of stories. That was the last craze for story collections, and writers read books like Airships by Barry Hannah and wanted to write stories.

Who was his readership at the time?

Yeah, so there were two types of people who were really into the book when it came out. One was the working-class Scots, basically. It spoke to them. The other was the kind of London and Manchester cognoscenti, clued-up working-class guys, who’d been through all the hedonistic, drug partying, football hooliganism, acid house, rave experience. So it was really a double-pronged thing. Then the stage play came out and toured, so it went from being a localized thing to a national thing. Then the film came out, so it went international.

Could Trainspotting be published in this day and age?

It would be very difficult, with the homogenization of culture, to publish a book like Trainspotting now. I don’t know if it would get published. It’d be a self-publishing job; then maybe a publisher would pick it up, after it got some buzz from there. When I first started writing books, you had fiction and nonfiction. Now, you basically write into marketing holes: you write thrillers, or crime, or romance, or science fiction. You shoot into these holes now. It’s very retail-driven. It’s very entertainment-led, rather than art-led.

How have writers changed?

I think the idea is now we all want some monetization. Back in the nineties, everybody was very happy to be paid. We got paid big sums of money for books, but it wasn’t the principal motivation. When I go to talk at universities now, it’s never, “I want to write a great book,” it’s always, “I want to write a bestseller.” Everything needs to be monetized.

Years ago, I read a profile of Welsh in The New Yorker and he joked that the only interation of the novel we hadn’t seen was Trainspotting: The Frangrance. Once I got to know him as a friend I joked that we’d still to see Trainspotting On Ice! Maybe that’s in the works.

No offense to Mr. Welsh (truly), but am I the only one who's bored to tears with this whole narrative that anything older than 10 years old "couldn't be made today"? (Mindy Kaling recently said that The Office was too subversive to be made now, for god's sake.) Tons of incredible, interesting things are being made all the time. Including subversive things. I just watched a movie from 2022 (Fresh) in which a guy kidnaps women and keeps them alive to carve them up and sell their body parts to cannibals. To name just the first example that comes to mind. Hell, if Greener Pastures had been written 20 years ago, there would be blog posts lamenting how it couldn't be written today. Guaranteed.

I'd be interested to know what Welsh means by the "homogenization of culture" that's supposedly happening now. Because we're in a time where a Pakistani-Canadian non-binary person can get an HBO series (again, just to name one example). That sure seems like the opposite of cultural homogenization to me.

‘Trainspotting’ was one of a number of books that got me back into literature big time when I was 15 or 16. I remember getting it and a copy of its sequel, ‘Porno’, from the store HMV. Binged through the two books, loved them, then went and read the rest of Welsh’s work.

It’s depressing but not surprising to see that Welsh thinks there’d be some issue with ‘Trainspotting’ getting published today. The self published book that later gets picked up by a publisher if it gets enough attention is an interesting topic. Do you think that’d be a something you’d be interesting in discussing at length in a future post, Chuck?