Exhibit A:

Chicago 2007, on the tour for Rant I was lodged at a boutique hotel in the Loop, downtown. In the Monadnock Building. To the present, the past always seems absurd; how to sell rooms to travelers, hotels once boasted Author’s Suites and Haunted Rooms. In 2007, this hotel offered guests a goldfish in a small bowl. Soon after check-in a bellman knocked at your door and presented a glass bowl the size of a softball, containing a single goldfish. This gimmick was pitched to give you company, comfort, a pet to make you feel less isolated and trapped in a small hotel room, far away from friends and family. Business travelers got chocolates on their pillows. They got minibars filled with booze, cable porn, and in 2007 they got a goldfish trapped in a bowl so small the fish could hardly turn around. The pet version of a one-night stand. No heart-warming sight this, to be trapped in a room staring at a trapped fish. Nor the next day, to step into the hallway and happen across the maid’s cart heaped with fresh towels and small soaps, and on the lowest shelf, tucked away, were rows of glass fishbowls, each containing a dead goldfish.

What to do with such absurd sadness? I turned my goldfish into the story Bait. You see, well, we’ll get to Nathaneal West, and Tom Robbins and Shirley Jackson, and Joseph Heller, and Nora Ephron, and Amy Hempel and E.B. White, and Fran Lebowitz, and, of course, Kafka. We’re coming up on the hundredth anniversary of Franz Kafka’s death—June 3rd, 1924—and journalists everywhere are hanging stories on that peg.

You see, during the 20th century, every writer aspired to write The Great American Novel. Artists set their sights on The Great American Painting, so much so that when Georgia O’Keeffe painted her first famous cow skull, she jokingly added red, white, and blue stripes to the background as an afterthought. And, of course, no one got the joke. Instead, they called her prank brilliant and profound and a brilliant, profound statement about the American West and the closing of the last frontier. The Great American Painting. And Georgia O’Keeffe laughed all the way to the bank.

People called The Great Gatsby The Great American Novel. As they did Edna Ferber’s Giant, and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, and everything written by Jack London. But by the era I was born into, well, a big dog couldn’t simply find himself alone in the arctic night and howl until he made contact with a pack of Alaskan wolves and then run off into The Wild to live happily ever after. No, we’re all that fish in its tiny bowl, waiting to die and be replaced by another fish.1

Exhibit B:

Los Angeles 1969, Sharon Tate is thirty-four weeks pregnant and uses a small trowel to dig holes around her rented house at 10050 Cielo Drive. It’s August 8th, and she’s due to give birth soon. Her husband, the director Roman Polanski, is setting up his next film. Her former flame, the celebrity hairdresser Jay Sebring, is stopping by later. Sharon and Jay and friends are going out to dinner at the Mexican restaurant El Coyote later that evening. But for now she’s hurrying to plant dozens of marigolds and daisies in the gardens around her house so she and the new baby can relax and enjoy the flowers, later on.

By 1972, everything seemed to have fallen apart, the Vietnam War, the Watergate scandal, the Middle East, Sunday Bloody Sunday, the famines in Africa and Pakistan … insert litany here.

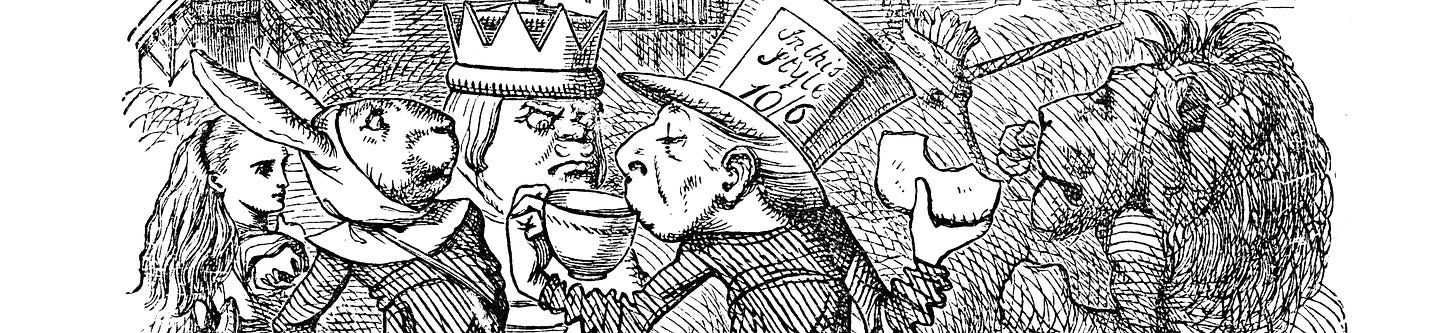

Dollars for doughnuts, that’s the appeal of Alice in Wonderland. Here a small child finds herself surrounded by the absurd. Her life’s in danger. “Off with her head!” The scale of things shifts as one minute she’s tiny and the next she’s enormous. Even her own body is beyond her control. Still, she’s got to be with it. She can’t reason her way out of paradox and hypocrisy and non sequiturs. No, all the power is held by irrational lunatics, and Alice has just got to make the best of things. In turns, she might be terrified or annoyed, but ultimately she’s just got to relax and accept the complete absurdity of the world. At least for the present.

For a child trapped in an unstable, combative household or school, Alice’s survival shines like a beacon of hope. For a child who can’t sleep nights, let’s say. Or a child menaced by bullies, but a child told, “Go to Sleep!” and, “Go to School!” and helpless in both circumstances, well, Alice is a role model.

As is Tod Hackett in The Day of the Locust.2 A recent college graduate, he finds himself designing costumes for a movie studio, in Hollywood, a world that runs on turning dreams into a canvas reality, driving each of those dreams to its conclusion, then throwing the dream away. Witness the bulldozers constantly scraping the earth bare of palaces and temples and pirate ships, and cramming all of this architecture into mounds of rubble overgrown with brambles. In the Nathaneal West novel, even the people on the streets of Hollywood are worn-out dreams. They’ve worked a lifetime, waiting to retire from some Midwest city and move to the paradise of Southern California. They’ve expected so much, deferred so much, that nothing will make them happy now. They walk around in costumes, in yachting caps and tennis whites and Tyrolean jackets, and boil with rage about having traded their lives for this lie of boredom. I read The Day of the Locust when I was in sixth grade, which would’ve made me eleven years old. It was the second time the world had ever made sense to me.

The year my parents told me that Santa Claus was a lie, that was the year I got my first pair of eyeglasses. That year, the world first made sense. People had faces. The teacher was writing words and numbers on the chalkboard. The next big revelation was The Day of the Locust, which taught me: People make shit up. People make shit up, and then they forget they made it up! Forever after, people act like their made-up shit is real. My best recourse wasn’t to argue with them. My best recourse was to watch and listen, be polite and to survive like Alice and like West’s protagonist, Tod Hackett.

By seventh grade I’d moved on to the Tom Robbins novels.3 To Kurt Vonnegut. To Shirley Jackson’s short story My Life with R.H. Macy. To Heller’s Catch-22. To Ephron’s Porter Goes to the Convention. Call it a fable. Call it satire or allegory, the message was: Life is absurd, and to expect anything but absurdity is to court lifelong unhappiness.

Exhibit C:

Last week I was walking my dog in the Lone Fir Cemetery in Portland. A jogger approached me from behind and said, “Excuse me, you’re not allowed to bring dogs into the cemetery.” I explained that I had a doctor’s letter which allowed me to take the dog most places. The jogger said, “But there are signs. You can’t have a dog here.” It had taken me years to build up my courage and ask my doctor for this letter. To do so seemed like such an act of weakness, and I keep careful track of said letter. It’s always in my pocket when I walk the dog. Still, the jogger continued, “You’re breaking the law to have a dog here.” He just wasn’t going to let up. People shoot porn in this same cemetery. They openly sell drugs. They snort heroin and defecate on the graves and topple monuments, but this jogger chooses to lecture me, the guy in a boring London Fog jacket,4 in the pocket of which is the letter I begged from my doctor. Not to belabor the moment, but here I shouted him down. I threatened to shoot him in the head and to fuck his dead body. I chased him. In short, I was not Alice.

Neither was I Robert Syverten at the end of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? who howls along with the police siren as he’s being taken away to prison and execution. It’s nice to think of that exhausted, bewildered howling guy juxtaposed with the howling of the kidnapped, abused, and abandoned sled dog in The Call of the Wild. Both have been hounded out of society. Let’s all howl, every so often.

Then, think of the main character in the film Brazil, tortured by absurdity to the point where he’s retreated to a permanent happiness somewhere deep in his head.

Let’s all howl, every so often.

Maybe I should lump the novels of Hunter Thompson into Absurdist Existentialism. Novels or gonzo reportage, wherein drugs allow the reader to recognize the crazy, made-up shit that passes as sanity. Thompson can drop acid and stagger through the sights of Las Vegas like Alice through Wonderland. Or like Tod Hackett as he walks through the absurd standing sets on a Hollywood backlot. Or like Amy Hempel confronted by daily vignettes of insanity in New York City in And Lead Us Not Into Penn Station. Or Kafka, prey to a constantly shifting nightmare of bureaucracy.

There’s a note of absurdity in Gatsby when Nick Carraway refers to Gatsby’s vast ridiculous house.5 But nobody much talks about writing The Great American Novel, not anymore.

Exhibit D:

The following anecdote haunted Joan Didion. A magazine had sent her to report on the huge stores of nerve gas warehoused near Pendleton, Oregon, in the 1960s. As she was checking out of her hotel, the desk clerk asked her, “If you don’t believe you’re going to be reunited with your loved ones in heaven, then what’s the point of dying?”

So I’d throw Joan Didion into the same Absurdist Existentialism pile. You can draw a kind-of crooked line from Alice to Dada to the antiheroes of The Depression and WWII, then the absurdist novels of Robbins and Vonnegut, then A Confederacy of Dunces. The various Cacophony Societies celebrated this same societal crazy. Shit happens, crazy shit.

This is Absurdist Existentialism. To recognize the crazy and to embrace it and to not be stopped by crazy people. Even your own crazy, because you’re crazy, too. And most often you’re crazy because you made up something—you invented the idea that people are always rational—and then you forgot you invented that, and now you think it’s real.

For me, one well-presented journey through crazy—think of the earthquake scene in The Loves of the Last Tycoon, where a flood carries away all the papier-mâché landmarks of the world—well, a good dose of crazy brings the comfort that a trapped-and-dying goldfish does not. The Absurdist Existentialist novel is The Great American Novel. And the message of Alice in Wonderland is to take everything in stride. Even your writing. Even yourself.

Exhibit E:

When journalists ask my opinion of Kafka, here on the almost-anniversary of his death, I remind them how Franz Kafka was fucking eight women when he died. I say, good on Kafka. Life is short.

And if that seems like tying a nihilistic bow on the end of everything … Consider that another choice would’ve been to close on the image of the shadowy, whispering strangers that are even now tip-toeing up that driveway off Cielo Drive.

The whole tiny fishbowl metaphor reeks of van life and tiny houses, no?

From Wikipedia: (The critic) Lee J. Richmond argues: "With the exception of Nathaniel West's Miss Lonelyhearts and The Day of the Locust, McCoy's novel is indisputably the best example of absurdist existentialism in American fiction." It seems we must forgive Wikipedia for butchering West’s name.

Recently, in a movie theater, I saw a young woman behind the candy counter reading Another Roadside Attraction. Of course I had to ask, and she told me she loved it, and that she could hardly wait to read more. I urged her to see the movie based on Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.

A present from Mike, who would have everyone look like Jason Statham.

“On the last night, with my trunk packed and my car sold to the grocer, I went over and looked at that huge incoherent failure of a house once more.”

It’s always been my contention that when people try to enforce public rules that don’t have any effect on their life, it’s usually because they have a home life where they’re not respected and so try to force it on you.

Acceptance of absurdity and meaninglessness, or bitter disappointment. Just washed my Albert Camus shirt. The good news is that we still get to create meaning.

Once upon a time, I had a gorgeous London Fog coat that fit me like a glove. I left it with my brother and he abandoned it and Im still mad about it. I still check ebay for a used version of it but haven't seen one since. Maybe Jonathon Statham could sell me one?