Nothing beats a good mnemonic device. In 1998 when David Fincher was shooting the film Fight Club his partner — now wife, Cean Chaffin — introduced herself. “It’s chafe-in,” she said, “like jock itch.” And I’ve never forgotten that. Similarly in Barcelona in a taxi, Michael Chabon introduced me to his wife, Ayelet Waldman. Doing so he said, “I never say my wife’s name… I yell it.” As a testament to the power of those devices I recall not just the names but the circumstances of the introductions.

I am Ukrainian, hear me roar. Or maybe Polish.

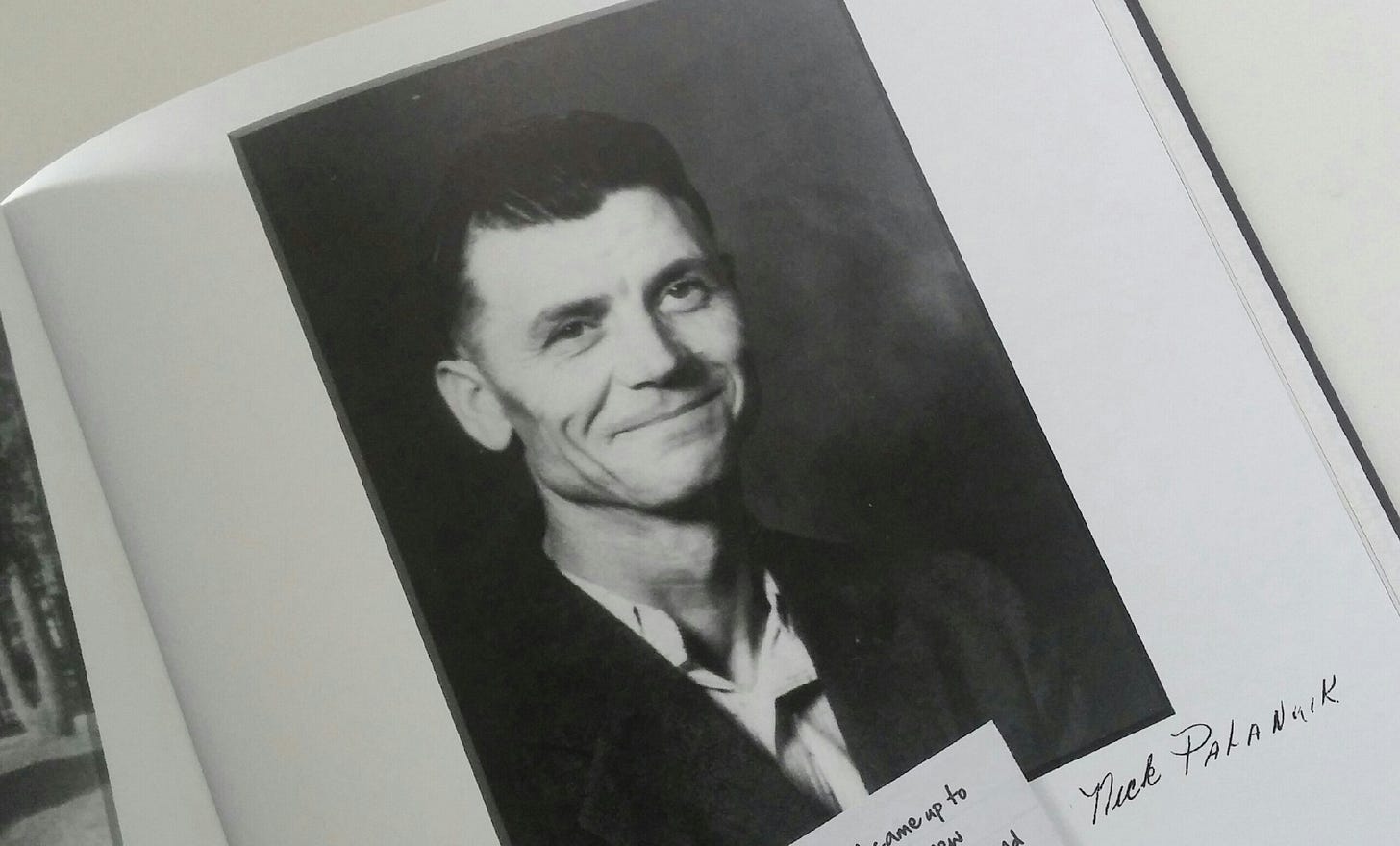

My father’s parents died when he was seven so I never knew them, not even their first names. Not until a family vacation when we drove to Idaho and visited their graves. To my surprise their names were Nick and Polly. Thus their names are an almost-mnemonic device for Palahniuk. Or as we pronounce it “PAH-la-nik.”

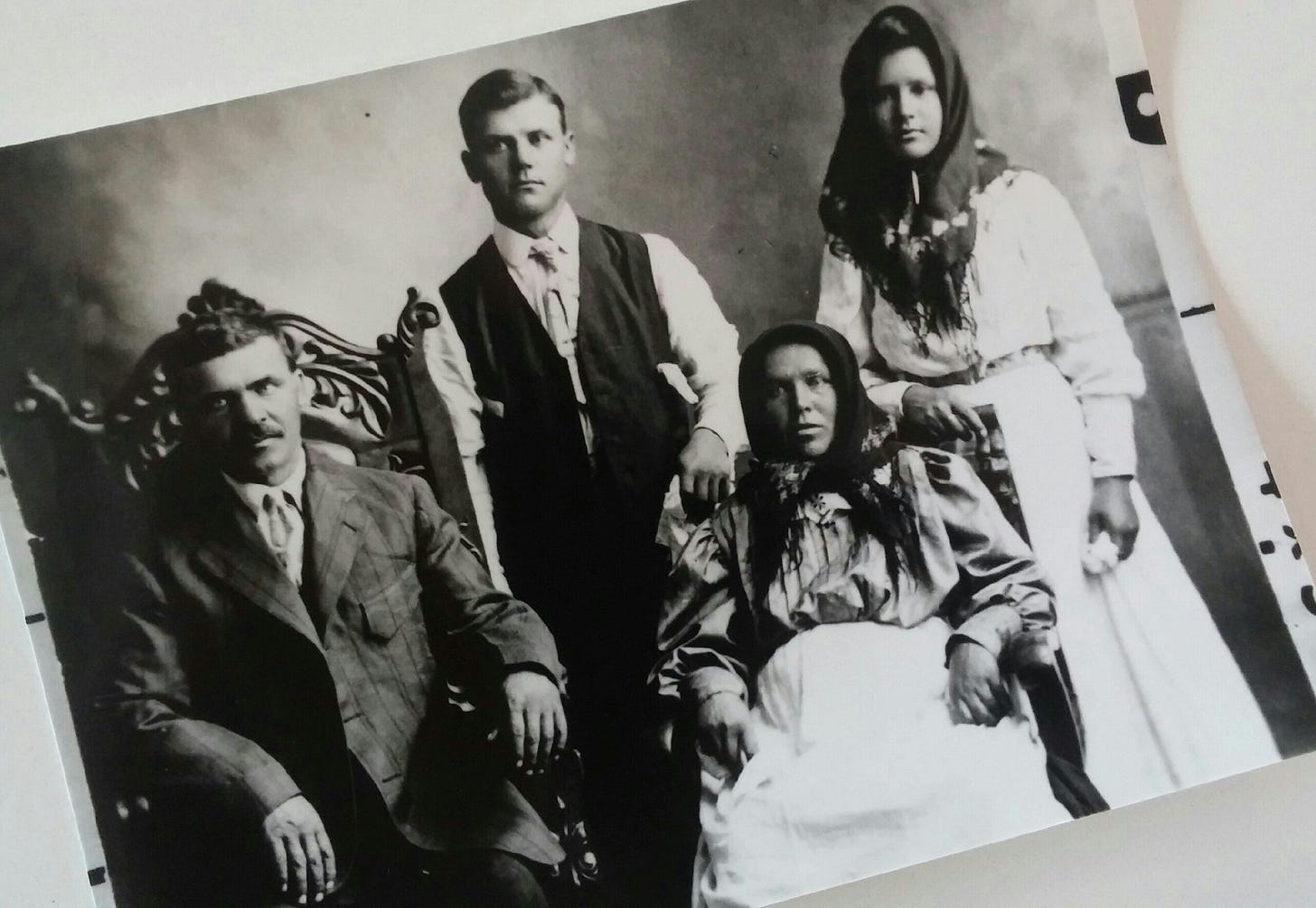

My grandfather, Nick, and his father, my great-grandfather, George, emigrated from the Galicia region of Eastern Europe in 1911. At different times, the area was claimed by either Ukraine or Poland so the family is divided about our national heritage.

Those original Palahniuks sailed from Bremen aboard the S.S. Saturnia, arriving in Quebec. They received their U.S. citizenship in Ukrainia, North Dakota in 1916. Born in 1939, my father tried to shed some letters from the family name, shortening it to “Palanik,”1 but when he enlisted in the Navy in the late 50s the government dug up his history and made him change the spelling back to match immigration records.

My dad’s small victory was that his first name, Frederick, was originally spelled “Frydryck.” We take our wins where we can.

A distant cousin of mine, the actor Jack Palance, was originally named Volodymyr Palahniuk. Not a name I’d like to have to hang on a theater marquee.

More soon. If I'm scarce, I'm still getting out the Pixie Packages. A lot of tape gunning and trips to the UPS Store.

I love this kind of story, Пане Паланюк (Mr. Palahniuk).

When you are a little kid, viewing the world through inexperienced eyes, there are certain things that don't register; differences that go unnoticed. When you are running around with your friends in the playground at primary school, you don't see black and white, poor and rich, foreign and native. You just see people.

Growing up I had a friend called Dimitri Kontogiannis. We became mates in reception class, at the age of five. I used to go round his house to play, and would stay and eat dinner, joined at the table by his two little brothers Yannis and Markos, both of whom had the same olive skin and dark features as their brother. Dimitri's dad was a tall, dark man with a thick moustache, who spoke with a strong accent. His name was Angelo and he worked on the ships. Obviously this is a Greek family; the clues were there! Yet it wasn't until I was about ten or eleven that I knew Dimitri’s family to be any different to any other in the neighbourhood. Even the name Dimitri Kontogiannis never seemed foreign to me. He was just my mate Dimitri.

I had another good friend in primary school called Tunde. He lived just round the corner from me, and most days our families would walk to school together; Tunde and I running ahead passing a football between ourselves, while our mums walked behind with our little siblings. Tunde was black. Both of his parents were white. I never noticed this; or if I did, I never questioned it; never asked my mum, 'How did two white people have a black baby?'

It wasn't that I felt it rude to ask; it just never seemed out of the ordinary; he called his parents mum and dad, so as far as I was concerned they were his mum and dad. When we were 11 Tunde went away. One day he was here, the next gone. But his mum and dad still lived round the corner and they had a couple of new sons, also black, and of school age. I asked how this couple had seemingly given birth to two 5-year old non-identical twins, and learnt that Tunde's mum and dad were foster parents who took in young African children in need of a loving home. Tunde had gone to be reunited with members of his birth family.

Years later, when we were teenagers, every now and then Tunde would appear unexpectedly in the local park and join our game of football as he came back to visit his second family.

There were other differences that I failed to clock growing-up; differences closer to home. Like how my mum's maiden name, Rayiru, didn't sound like it originated in the London that she grew up in. Nor did it register that my grandad's skin was darker than ours; that it was light brown. He spoke with a strong London accent and we never saw him as having anything foreign about him. He was called Kris - Krissy to his friends and family - and it was him that I was named after. I never wondered why we spelt our name with a K, or why Kris wasn't short for anything, like Christopher, or Christian; it was just Kris. It never seemed strange, either, when grandad talked about his brothers, Ramsay, Raja, Ranji and Rama.

I never had any questions about the turban-wearing Indian man in the black and white photo that hung on our living-room wall with all the other family snaps. I knew who he was; sure, he was my great grandad who had died before I was born. But I never knew his name. And it never clicked that if this Indian man was my great grandfather, then Indian blood also ran through my veins.

Then one night, not long after turning 30, I had a vivid dream. I was in India, in a coastal village with a deserted sandy beach and a beautiful turquoise sea. I was being introduced to people, left, right and centre and I was happy; so was everyone else. I had Delhi Belly and was constantly aware of exactly how far away I was from the nearest toilet, but it didn’t dampen my spirits. Tables of food lined the main path through the village; dishes emanating the most delicious aromas, as people offered me samplings of biryani and fish curry. Despite the condition of my guts, I tried heaped spoons of everything. It was all delicious! I was enveloped inside a feeling of utter tranquillity; one of being at home. I didn't want to leave. The dream ended on the beach, as I walked along the shoreline, feet in the water.

Two nights later the dream returned; this time it was even more vivid. After waking up, I was in no doubt as to what it meant: I was being called to India, to discover my roots. But which part of India was I being called to? I had no idea where in that huge country my great grandfather had come from.

To cut a long story short (I know what you’re thinking: too late for that!) a friend of mine who practiced genealogy helped me find out some stuff, such as my great grandfather’s first name, Rama. And also that my grandad, whom I had only ever known as Krissy, had anglicised his name from Krishna (I’m named after Krishna, the Hindu god. WTF!!)

Rama was one of those old-school immigrants who moved to a country, adapted and integrated, started a family, never spoke a word about his past life, brought his kids up in the culture of the land of their birth and then returned to his homeland at the end of it all to see out his final years. Because of this, no one seems to know too much about him.

I did learn that he was born in the south-western state of Kerala in 1893, and grew up next to the sea. I didn’t know this information when I had those dreams, but when I started exploring Kerala on the internet, I couldn’t believe how much the beaches resembled those my subconscious had conjured up.

According to documents, Rama’s profession was actor and dancer. He came to England by sea in 1926 to perform, and later that same year he married his English fiancée, also a dancer and stage performer, and they had kids and the rest is history.

Years later, with Rama in his 60s and in failing health, he and my great grandmother returned "home" to Kerala in India, where a house next to the beach was built in which they could live out their final years together. Rama died there in 1969 at the age of 76.

Now that I knew all this, I was sure that the dream meant I had to go there. And so I did. Except, the thing is, I have ADHD. Off the scales ADHD. Which means I made no plans at all, just jumped on a plane (dragged my wife along for the ride), jumped on some trains until we found ourselves in the jungle. Jumped in a rickshaw and rode further into the jungle. Then realised I had zero clue wtf I was doing. I was just lost in a jungle in India, with my wife, in a rickshaw.

I didn’t find any relatives. I did get a bad case of Delhi Belly. And a story. Thanks ADHD.