Let’s start with Ken. A coworker at Freightliner Trucks. Years before I sold any fiction, he got wind of me writing fiction and he never missed a chance to step up and ask, “How’s that little writing thing going?”

Ken had become an engineer because it was a sure-thing career, and he loved to lord that over us English and journalism majors now working in grunt jobs. He goaded me, and that only made me want to sell a book more. Even when Fight Club was published to middling sales in 1996 he kept up the put-downs, asking, “So when are you going to hit the bestseller list?”

No matter what I got done, Ken would find a new way to twist the knife. Angry and bitter, he seemed to hate being an engineer, but he’d chosen that career for security not fun.

When the film Fight Club launched, on one of my last days in that job, I overheard Ken telling someone, “Maybe I should’ve gotten a degree in English…”

A weird, sad moment for sure.

How’s this for an even sadder moment? Before I’d written Fight Club my boss took me aside and offered me his job. He’d worked all his life at Freightliner, from clerking in the mail room to managing his own department. He’d be retiring in a few years and needed to train his replacement. The promotion would set me up for life, but it would also eat up my life. To turn it down would be turning down a position my boss had devoted decades to getting. Nonetheless, I didn’t dream of managing people. I wanted to write.

And, no, I didn’t feel superior or vindicated hearing Ken. Or when telling my boss, no, I didn’t want that promotion. I just felt scared that I was turning down any secure future with, you know, health insurance and retirement and food.

This was the basis for the novel I’ll begin serializing next week. Greener Pastures it’s called.

In Greener Pastures I wanted to write about that part of your life when you’re torn between choosing the sure-thing career versus the risky dream.

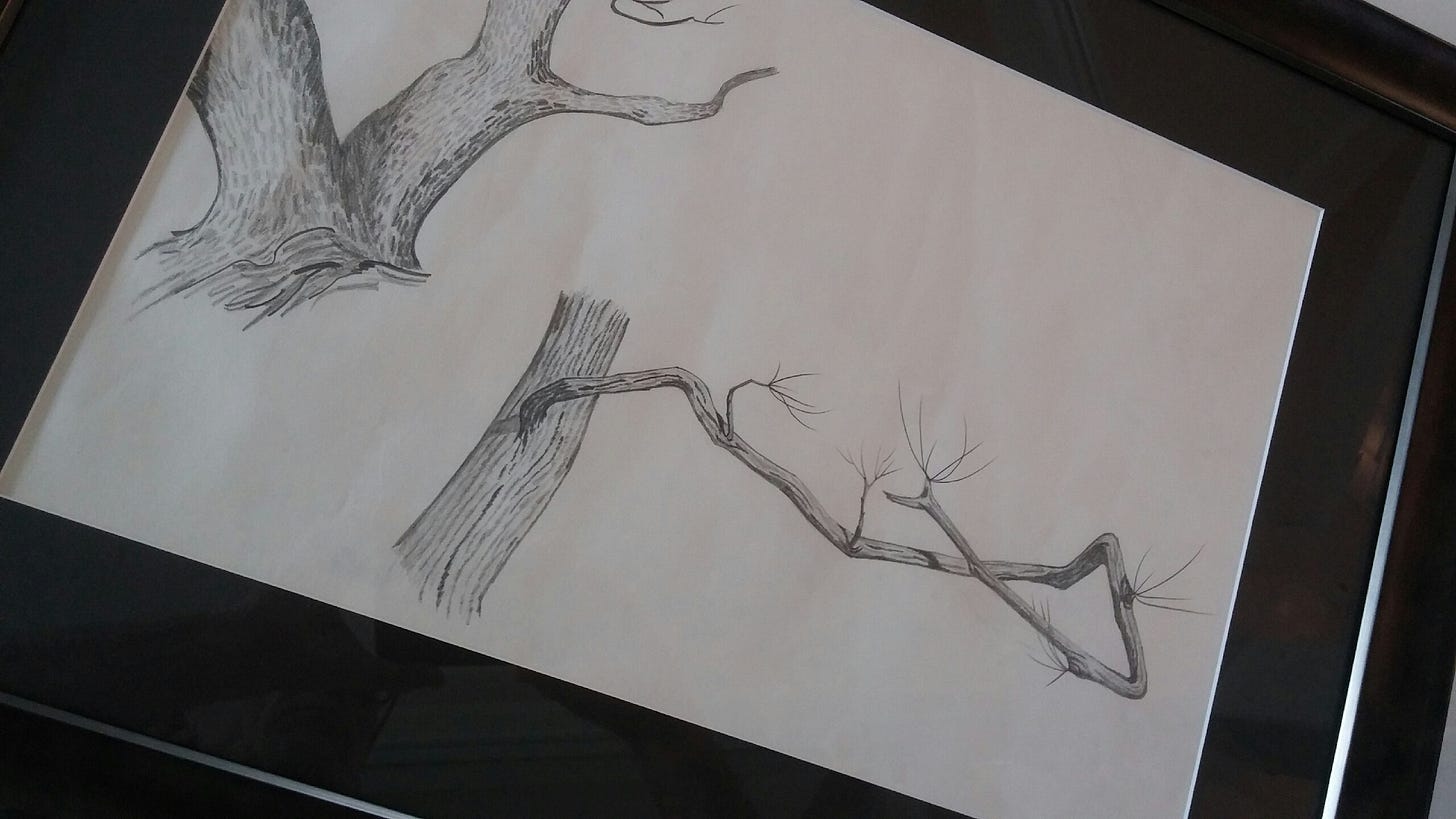

My mom, Carol Palahniuk, for example, had been a competent artist in her early twenties. She filled sketch pads with technically perfect landscapes and studies. Having four kids in six years derailed that dream, but after she retired she gave it another shot.1 In her sixties she went back to school, and we all asked to see her work, and she politely refused to show us. After her death we found her newer pictures, and they were a mess. So sloppy they looked like fingerpaintings next to the work she’d done when a young woman.

In Greener Pastures I wanted to write about that part of your life when you’re torn between choosing the sure-thing career versus the risky dream.

Seeing those sloppy watercolors and charcoals scared me. It seemed clear that some ability had faded. She’d missed an opportunity and could never regain what skill she’d had and had postponed developing. And I’d come so close to making the same mistake. Until I was twenty-six years old I’d planned to work and work and wait until my retirement to begin writing. All my life I’d been reading, so I figured I’d just naturally be able to sit and write perfectly once I could do so full time.

Sure, there are examples of people who waited and wrote successfully. There’s Alan Bradley who retired after a lifetime of engineering and wrote The Sweetness at the Bottom of the Pie. But I’d wager he’s the exception.

Besides, when you’re eighteen you’re expected to get so much done so quickly. We forget that terror. You’re expected to find a spouse, get an education, build a home, begin a career, start a family. You’re basically still a kid with a kid’s impulses, but the clock is ticking. And your entire generation is out to win the same prizes. To flub one detail feels like you’ll wreck the rest of your life. All the while the only natural powers you have – your youth and energy – are dwindling.

And even if you have a plan, an obvious talent, you’re scared that it might not be enough for you to survive. Especially if you’re from a working-class family, afraid of sliding back into poverty. I wanted to write about that, that window of time when you’re torn between the sure-thing career that you’d soon hate, and the risky career that you’d love for years to come.

That’s Greener Pastures. If at the age of fifteen someone had covertly offered a huge sum of money for you to devote your life to some high-status-but-boring job — would you have sold out? Your parents would get much of that money. They’d be set for life. You’d get a high-profile, powerful position in the world, but it wouldn’t be your choice.

At fifteen, facing all the world’s expectations, would you sell out?

It’s a one-time offer. Take it or leave it.

Or could you anticipate the lifetime of frustration waiting for you in that glamorous dead-end career? Would you trade your dreams and life for complete safety and security and boredom? That’s the basis of Greener Pastures.

Look for the first chapters in the next few days. I’ll drop a chapter each week after that. The first few are free, just like with heroin. Thank you for giving it a read.

A confession, here. As I began to sell my work on a regular basis I grew horns on my head, and a tail, and I became a raging demon. My mission was to push people toward fulfilling their dreams. If they had a hobby they loved, I’d push them to make it their career. If they enjoyed singing, I aggressively “coached” them to go professional. My own success seemed so surprising and unlikely that I couldn’t see why others didn’t reach out for more. By buying my mom lessons and art supplies, and paying for my friends to take acting classes, I thought I was helping. Really, I’d shape-shifted into a well-meaning bully.

I’ll never forget the day I told my dad I was switching my major to English. It was Christmas because I’m a sucker for drama. My whole life my dad had pushed me to focus on finding a good career. He said, “Go to college. Find a job. Make sure you have insurance.” The rest I just had to guess about. That day, I told him I was dropping computer science, a major he largely endorsed. I remember his first question was, “What are you going to do?” I told him I didn’t care because I loved reading. He never said so, but I knew he was disappointed in my decision. I was in my mid-twenties at that point and I hadn’t done a fantastic job of managing my life. I spent the next eight years finishing my BA, only to feel like I had failed. I had no plan. So, I got an MFA. I’d decided I wanted to be a writer. I moved a thousand miles away from home to go to school. Too far for either of us to visit one another. He was diagnosed with lymphoma my final year in the program. I was devastated. I ended up writing a shitty novel as my thesis. A book about a man who abandons convention after his own terminal diagnosis. I didn’t realize it at the time, but the whole thing was a self-induced therapy session. My dad died due to complications during his treatment and I never saw him after I left to be a writer. I was too poor. He was too sick. After I graduated, I could have applied for university positions like all my cohorts. Gotten that security my dad always wanted for me. But I didn’t. I didn’t want to give up on my dream. Even now, I’m barely scrapping by on the meager earnings I’m able to produce doing what I love. All so I can have more time to write. Because I fear the same artistic fate as your mother. It’s terrifying to struggle to live, but I’m proud of myself for making the decision. I like to think my dad would be proud too. Either way, I’m glad everyone is here. Being a part of this community makes me feel better.

Some years ago, I took a job teaching an art program with the developmentally disabled. I’ve never done that type of work before in my life. I had no idea what to expect. I had one friend in the same art field and I would sit in with her classes at first. Each client was so unique and so truthful in their emotions that I could relate, easily. There were so many good days and of course, there were bad ones. You learn quickly— you cannot manage chaos— you have to flow within it.

A few clients took to me right away, they saw I could draw and create. One client loved Halloween and spooky things. We would sit in the art room and he would tell me what he wanted to draw, while he repeatedly, tried to scare me. I would pretend that he did and let out a little scream. We would pretty much do this all day— I loved it. I enjoyed the clients that also spoke in their own way and would crack themselves up. Another client always had an elaborate story about what she had for breakfast— she was also diabetic, so she would be telling me her “dream” breakfast. She also would take and hide every marker we had. She had a best friend she watched out for, took care of her at lunch, she was non-verbal loved her blocks and music. She drew the most colorful circles over and over again. It made her so happy.

My biggest take away from the job was when I started teaching them my main profession, screenprinting. You’re basically doing the same process by hand, over and over again. Probably, why I love repetition of jokes, the process of making jams, and sewing. There’s a safety in it that I didn’t have growing up. I didn’t have a stable life at all. No heat for months at a time. Not knowing if the electric will be shut off soon, or simply what we would be eating. So, I started printing t-shirts with the clients. One non-verbal client who LOVED his coffee, would hang around and watch. He did the same when I would start sewing projects with my group. We seriously made some outstanding pillows. I would ask if he wanted to help out— always an elongated—- Nooooooo, but I noticed he was smiling everytime I asked. So, instead of asking, I just put his hands on the squeegee, with mine and he pulled his very first t-shirt. He was one of my best helpers. We developed a rhythm to printing— he would pull a shirt, help me take it off the board, then, walk the hall, come back and repeat. I also told him terrible Dad jokes that he would crack up about. I miss all of these folks so bad.

Before I started this job, if I didn’t pick up a new trade quickly, I would give up. Or I would just walk away from projects incomplete because I couldn’t get past my ego. But, these folks— who in their own life, kept trying, kept learning, continued to never give up— they broke my ego and despite horribly failing at some projects we did— I didn’t give up—- they taught me to laugh with them. Laugh at the mistake and get this—- I could TRY AGAIN. and again, if I needed to. They broke me, but fixed me stronger and for the better. I have never in my life thought my fails were funny. I would beat myself up for not being good at something right away—- but now— a fail isn’t wasted time or effort anymore— it is something I proudly laugh at now and think of MY teachers, from that group.

You never know where your next life lesson will come from…ever.

I’m grateful for this forum. It has brought me back to something I needed most— to tell the story. Alright— enough with the mush. I’m getting all wet in the eyes.