As promised, here’s some feedback on a few of the stories posted to the Comments section this week…

Thank you for posting links to your work. Each week I’ll choose a few to comment on. In most cases I’ll try to print them so I can carry them around and reread them, and mark up the paper with my notes. This is no quick process, and I need to collect my thoughts—in parking lots, at the gym, outdoors—and reread each work many times. It sucks, but several of the pieces I chose this go-round wouldn’t print, so I chose alternates. Otherwise, I more or less started near the top of the Comments and worked my way down.

That said, let’s make a start. Please, Touch the Art by Remy Lazarus

What I liked (a lot)…

This piece perfectly nails the artist/writer/musician’s desire to forever change the audience’s perception. David Fincher has said “Art should leave a scar.” And the art that endures begins as provocative art. The reveal here: that the art is doping the viewer with radioactivity is—brilliant. If I hadn’t known the writing prompt, it would’ve caught me by complete, stunned surprise. Besides inventing a good voice, this kind of surprise reveal is the toughest task in writing. And here it’s so simple and so inevitable, but it still catches me off guard.

With that in mind, consider that your “horses” or themes are: changing perception, impacting the audience, and the nature of art creating authority through controversy before it becomes a commodity. Rather than open with a description of the narrator’s previous work, why not establish precedent by giving us the original value and subsequent values of controversial art such as the Piss Christ and Fountain and Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963 - 1995 ? You can establish the cultural precedent with examples that the reader knows, and thus avoid having to open with description of fresh, static objects. Plus, this demonstration of body of knowledge will create head authority for the narrator. Again, give the original price of each work, then give the estimated current value. Consider how this misdirects the reader into thinking the narrator is all about making money.

You can broaden the themes by describing how historically people reacted in shock and anger to new artwork, for example the derision leaped on Stravinsky by hectoring concert-goers. Or, the charges of obscenity lodged against Mapplethorpe. All of this audience push-back creates dread about the narrator’s new work. It uses existing cultural precedent to suggest we’re building toward something shockingly worse. For more, check out Stendhal Syndrome.

If you want to risk a tangent that will confuse the reader for a beat, try this. Make the observation that many everyday items were later found to be deadly. Cyanide-green wallpaper, for example, or Fiestaware sugar bowls glazed with radioactive uranium-red coloring, or radium watch dials. Dig a little, it’s easy. These specific items will stick in the reader’s mind and only make sense once you reveal the deadly nature of the artwork. Again, they build dread. By using specifics you can keep everything in suspension until it jells at the last moment.

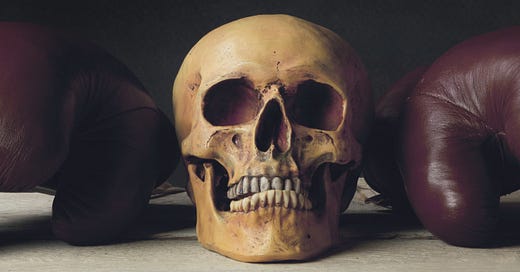

Now, make your artist a total dick. Scrap the reference to me—I’m scaffolding, this is your moment to shine—make it your narrator’s intention all along to dose people with gamma rays and bake them alive. We’re forced to control our impulses all the time, so this is your chance to unleash the psychotic that touches the psychotic in others. Go crazy. Do the despicable thing… but for the noble reason: ART.

How to get away with this? Easy. Make the museum goers appear like even bigger dicks. They’re doing selfie duck faces. They flash their tits for the photo. They arrive with hand-lettered signs that read “Hiroshima or Bust!” They flash gang signs. They’re obviously trivializing the tragedy of history, so it’s only fair game to kill them. The reader will want to see them killed, because you’ll show them as callow and heartless and vain. The more vain they are, the more they return, thus the faster they die. We like that. Especially if they’re rich, we love to see rich people used and discarded.

Besides that, show in dollars and cents what this artwork is priced at—put it in a ritzy gallery, not a museum—and in complete bitter irony show how the prices climb once it’s infamous. That can be your clock—what ticks away the passage of time in the story. Another clock can be the gradual decrepitude of returning patrons. Long before we know the nature of the artwork, we need to see teeth falling out, hair falling out, open sores and whatnot.

You might also touch on the sad irony that starving artists created things that now only the super-rich can own. In that way, this might be the narrator’s revenge against the commodification of art.

What I’d like to like more…

Now, let’s talk context. The context—Who’s telling this story? Where is it being told? Why is it being told?—is crucial. Perhaps it’s a deposition being given before a trial. Or it’s a deathbed confession as the narrator succumbs. Think of the film The Social Network or Amadeus. The context will decree your structure and transitional devices, those elements that will allow you to jump around in time, and to change the focus in a beat without losing the reader. Think of those newsreel reporters in Citizen Kane. The context may also decree the tone of the language. Think of the legalese I used in the short story Prayer.

Also, avoid stating things in summary, “Most of my installations have been polarizing…” Instead, give examples—either historical ones or ones you invent—that allow the reader to make the judgment “polarizing.” Okay?

In summation…

This is such a bold, amazing concept. It demonstrates how people use art as their backdrop, they trivialize art and tragedy, but the justice comes when the art gets its revenge. And I’m impressed how you can do all of this in so few pages. It’s an excellent first draft, but now I’d like to see the ideas demonstrated and dramatized more. A drop-dead terrific concept.

Now let’s take a quick terrier break:

Now, on with the show. The Stuffed Crust Conquistador by Matt Perky

What I liked

Do you remember the sequence in The Grapes of Wrath where the characters install new piston rings on a car? In order to compress the rings, they wrapped each ring in a thin strand of brass wire, explaining how the heat of the combustion will melt and burn away the fine brass. I read that book in seventh grade, and I still know that trick about doing a roadside ring job. That’s the excellent way that a well-depicted physical process sticks in the reader’s mind. And that’s what I loved about this piece of work.

The moment the author listed several items including CB radio antennas, I thought What? I was already hooked by the suggestion we were going to rob burial mounds.1 But the antennas were such an odd item that my mind scrambled to justify them—Were the characters going to use police radio scanners? Was this story set in 1977?—that specificity and strangeness created an unresolved tension. Once they began the physical process of hunting for burial sites, and they used the antennas as probes, I felt a huge rush of comprehension and relief. Such moments are what make reading wonderful. Thank you.2

Add to that the authority the author creates in describing the various distinctions of “feel” for when the probe strikes stone or wood or bones. It’s such a visceral knowledge, only your bones and nerves know that feeling. Twenty years ago, I interviewed the owners of the Portland landmark Hippo Hardware. They said how a much older junk dealer had taught them as very, very young men how to tap a painted object and detect whether it was brass or steel or iron or bronze despite layers and layers of dirt or rust or paint. Their skills were such that they could tap an object with a fingernail and tell the alloy proportions. By touch, they could tell brass plating from solid brass. It’s this exact same physical body of knowledge that the grave hunter demonstrates. I can’t wait to hear about faking pottery and arrowheads. When was the last time you hear the word “knapping”? All glorious stuff.

It’s also a wonderful way to “peek” into the underworld or the afterlife. We see the probe go into the ground, but it would be good to see it slowly extracted—even from a failed delving. In effect it’s the rope thrown into the closet in the film Poltergeist, a thing that’s gone into the land of the dead and emerged intact. Does it have a smell? It’s no doubt been stabbed into numerous graves, so it’s freighted with history. This becomes an object that could kill a copperhead (which I’d wager is the buried gun) or be stabbed through the heart of a character. If anything it might be stabbed into a grave and then, slowly, slowly, slowly, inexplicably be pushed up and out of the ground.

Again, this story demonstrates how a simple, common object can become powerful. The author could take that object and make us believe anything. That’s a great trick.

If anything, I’d like to see the object and its similar probes particularized more. Some are considered “lucky,” or have names associated with their success, or? The whole process suggests dowsing for water or the automatic writing at seances. All from an old radio antennae—not to mention how antennas are used to catch invisible signals from space. It all gives me chills.

What I’d like to like more…

Because we quickly get to the antennae as an object, and invisible signals as a theme, I can accept the radio in the opening. The radio on the workbench. That’s kind of masterful to be honest.

Consider not cutting from that to a long-ago scene in an airport. And then to a perilous tree. They seem a little far afield from your horses (themes). I’ll buy the gas station hotdog metaphor—love those acrid hotdogs—because it supports the garage, driving, blue-collar vibe. But stay closer to your opening, grave-robbing scene.

Also, don’t hurry to tell us about the cancer. Give us a chance to dislike the characters before they too-quickly redeem themselves. Readers can follow an unsympathetic character so long as he or she is clever, and you’re showing us a fresh world with people who are smart about what they do. Don’t rush to justify their actions because you’ll lose the tension and conflict of readers admiring grave robbers despite the fact that they’re… robbing graves. Keep that approach/avoidance energy going.

This is a small point, and while I loved the description of poking metal through old bones, I’m not sold on “Tinkertoys.” Do you mean the sound of breaking a Tinkertoy in half? The simile might be too archaic for most readers. Give it another go, okay? Consider, “It’s the sound of when you break apart the two wooden chopsticks at General Chang’s before digging into your noodles.” In other words, look for a newer comparison. That simile should describe the narrator’s life in that moment. So you could also go with, “It’s the sound of your older brother, Tobias, sticking a red Tinkertoy into your hip and snapping the wood off under the skin.” Again, description should describe the describer. Well, and describe wonderful dead bones.

In summation…

I would so love to read this book, but please keep your focus. You can use everything—the airport, the tree, the cancer—but put them in places where they’ll work without drawing our attention away from the goal of the chapter.

Time for another quick terrier break:

Now, back to work. Destined by Greg Eidson

What I liked about this story…

Again, the process is arresting. Rice Krispies will never seem the same, and that’s exactly what an author wants to do. But consider slowing that process for a beat. Is cocking the gun the “snap”? Is pulling the trigger the “pop”? Please don’t rush this, it’s too important. It’s central. In that same vein, consider a moment when the father somewhat embraces the boy to demonstrate holding the gun—just to step on the physical aspects. At some point a dad’s physical contact becomes icky, and such a moment can depict dad’s health and age as well as the son’s.

It was also wonderful that “Tara” was the guidance counselor. But consider making this reveal more gradual. If you began by referring to her with a courtesy title such as “Miss Thompson” it would allow the reader to think she was a teacher. Later you can reveal her to be the guidance counselor. Finally you can create the sense of intimacy and attachment by calling her Tara. This brings our focus in more slowly.

The bruise was also effective, but it’s tough to be aware of something within your clothing. If the butt kicked back hard enough, we might see blood bloom through the fabric of the narrator’s shirt or pajamas. Then, when the father says, “Feels good, don’t it?” and fails to react to the sight of blood—the moment lands all the harder.

With that, unpack the smell of gunfire. It smells like July 4th, right? Like the jazzy smell of gasoline when you’re filling the tank? Unpack the warmth of the gun in the cold. I realize that Jason is medicated, but you need to go into greater detail in regard to the killings. Friends of mine who are first responders tell me that in mass-casualty triage situations they side step the victims who are “doing the funky chicken.”3 By this they mean the death throes of people who are beyond saving. In my time doing volunteer work at a hospice I watched people dying in fits of shaking and spasms. As always the best way to describe your narrator is in how he describes the world around him.4

What I’d like to like more…

On past book tours, Doug Coupland, the author of Generation X, would stage a neat trick. He’d ask the hundreds or thousands of people in the audience to exchange phone numbers with their seat neighbors, and then to call each other and not answer the calls. As a result the auditorium would be filled with a cacophony of bells and ringtones, a terrible din.

“This,” he’d say, “is how it sounded to first responders when they walked into Columbine High School.” He’d explain that countless phones had been dropped or were still on the bodies of the dead or wounded, or were locked in lockers. And countless parents were trying to reach their children. The empty school was a nightmare of phones ringing. That was the backdrop to the tragedy.

When Coupland pulled the trick, it left his audience breathless with horror. It was incredible, how he made the mundane suddenly terrifying.

That’s what I’d like to see in this piece. A fresh avenue into the story that makes it seem new and even more upsetting.

Thirty years ago when I was writing Fight Club in Tom’s workshop, he’d invited the writer Karen Karbo to speak to us, his students. She heard me read the opening scene from the book and said, “I hate it when a writer just says ‘the gun.’ Be more specific. Particularize your important objects.” So I’d gone to The Anarchist’s Cookbook and read the bit about drilling holes in the gun barrel to create a so-called silencer. This new bit of detail made the scene that much better and hinted that the narrator had a dangerous body of knowledge. And built authority.

That said, consider that the narrator would know more about guns. And the narrator would use that knowledge rather than stating “the gun” or “the rifle.” Don’t overload on terminology, but just find some more specific terms to use.

In summation…

You have some breathtaking moments. My ethos is that a writer can depict anything so long as he honors the story by going into detail. We’ve seen too many Hollywood movies where people die bloodlessly from a single gunshot. In contrast, check out the final few minutes of the film Heavenly Creatures and see how slowly and lovingly Peter Jackson kills the mother with the brick. It’s monstrous, but it makes every other death scene look like bullshit. What helps is the sweet music laid over the violence.

Consider the nurse in Misery who can butcher people but can’t swear. You can create big tension by using a sugary voice to depict violent actions. The mismatch paradox allows your reader to be with the awful, yet allows you to craft more realistic scenes of mayhem.

In the future I’ll continue to refer back to that post for additional stories on which to give feedback. For the time being, please continue to post links to your work here.

In the future—if you revise work, maybe using tips you’ve collected here—simply post the newer version and delete the earlier. In a while I’ll make a new post to request writing samples, and we’ll move on to that post for submissions.

Full disclosure: During my childhood the Columbia River was being dammed, and the rising upstream waters eroded countless ancient burial grounds in my area. As a result you could walk along the banks of the Columbia and Snake Rivers and routinely find human skulls and flinted tools. The original families in my hometown usually had a collection of such skulls and ceremonial knives they’d found unearthed by the flooding. Spooky stuff, indeed.

In a similar vein, consider the Denis Johnson story Work from the collection Jesus’ Son. In it Johnson shows us how to steal copper wiring from vacant houses and sell it for scrap.

Yeah, that’s what they call those final moments of “active dying.” The funky chicken.

For example, you hooked me when you mentioned Moses Lake because we played them in high school basketball. We’re not triggered by new things, we’re triggered by echoes of the past.

You read your favourite author’s work for years waiting for a way to tell him how much it changed you. And then you end up with that very same author going to the gym with a printed copy of your work folded in the bag and giving you the most detailed, constructive feedback you’ve ever received.

Chuck, that’s priceless. Thank you for doing this.

Mister Palahniuk, I have been such a long time fan, to even get a bit of brief attention on this site means the world to me, to have you read a piece of my writing has already made my year, but to receive such in-depth and fantastic feedback is beyond what I could have ever hoped for. The notes you gave put a smile on my face as can imagine all the parts you propose amping it all even more. A bit embarrassing to say I can’t even use enough words to express my gratitude but thank you so much. I am forever grateful.