First a story about Tom’s workshop …

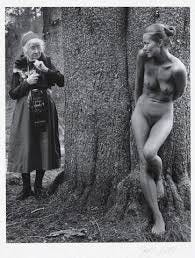

In 1991 or thereabouts we arrived at Tom’s house for Thursday night workshop, and Tom had a guest. When Tom introduced her as Twinka Thiebaud, I’d no words. Here was one of the most iconic people of the last century, sitting at the kitchen table in Tom’s half-finished house. As the subject of Imogen Cunningham’s most famous photograph, she’d been the first woman to appear full-frontal nude in Life magazine. She’d been a confidant of the playwright Henry Miller. An enormous painting of her in the Dallas Museum of Art1 had attracted a man who claimed to be in love with the work, and who arrived everyday to sit and stare at it for possibly years.

And here she was, chatting with Tom and us, and we were expected to chat back. Of course I knew who she was. Anyone who’s seen the Cunningham photo would know Twinka on sight:

When Tom formally introduced us, I stammered and said, “This is like meeting Colonel Sanders.” I meant no disrespect. The moment you meet someone so iconic, a person you’ve only known as an image, it’s … awkward. Until that moment, it had never seemed possible that people made the culture around us. Coming from a small town, I’d never met anyone celebrated. Half the power of Tom’s workshop was simply to sit in the presence of a person who’d published a book. Tom’s physical existence made that dream seem possible. Twinka laughed at my clumsy comparison, and we got past the rocky moment.

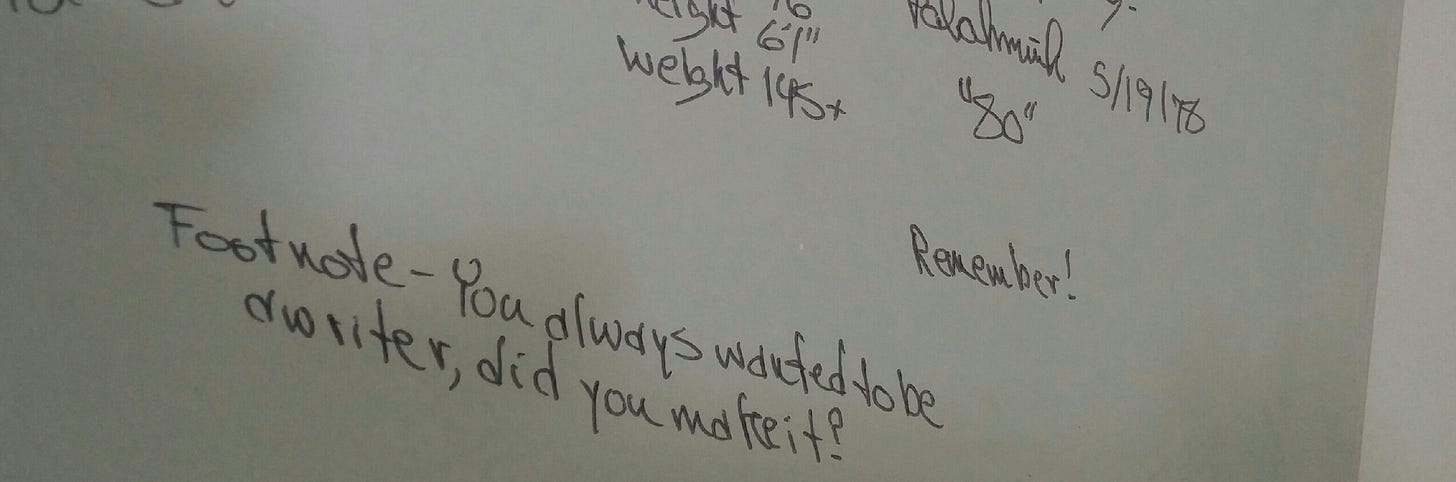

That said, more recently I was unpacking books, and among them were my old high school annuals. In the photos we all looked goofy, to say the least. As I paged through my sophomore year I found a note I’d written on the inside of one back cover. It was dated May 19, 1978 and was titled: “To the Chuck of the Future.” It gave my height as six-foot-one (which is wrong, I’ve never been taller than five-eleven) and it gave my weight at 145 pounds (which is probably right because I’d had mononucleosis that year). I’d been sixteen when I’d written this, and I’d long forgotten the note existed. At the bottom was a question:

“Footnote—You always wanted to be a writer, did you make it?” (see above)

Noted, my handwriting is awful. That same year our local AM rock station held a contest, the “KALE Radio Mystery Mom.” Among the various clues given in the weeks leading up to Mother’s Day, one stated the mystery mom was a recording artist. That year the humor writer Erma Bombeck had recorded her first comedy album so I took a shot. Erma Bombeck and Dave Barry were staples in our local newspaper, and we read them every week. And I won. My prize? A fifteen-hundred-dollar silver tea and coffee service, just what any teenager wants.2

Yes, this is a jumble, but jump forward to 1996 when the novels Infinite Jest and Fight Club were first published in Italy. The literary pioneer Fernanda Pivano—who’d been a colleague of Hemingway and had translated and introduced the American writers of the 20th century to Italians—published a feature in la Repubblica about the future of literature in America. In big, bold headlines she wrote that American fiction would belong to David Foster Wallace and Chuck Palahniuk. I was stunned. You don’t get many moments like that.

Later, during a tour in Italy she introduced me to an audience in Milan. As she spoke, the translator leaned close and whispered to me what she was saying. I’ve mentioned this translator, Paolo, before. He whispered, “And now she is talking about your beautiful wife and your eight beautiful children …” Still, God bless her for trying.

Jump forward to 2008. I’m staying at the Beverly Hills Hilton for the press junket to promote the film made from my novel Choke. Room service arrives with breakfast, and there on the front page of the Los Angeles Times is an obituary for David Foster Wallace. He’d killed himself the day before, only a few miles away. We’d never met, but we knew the same people, in particular the editor Gerry Howard. These mutual friends have told me stories. Wallace’s adjustment to public life was just as stumbling as my own.

What caught me by surprise was his birth date. David Foster Wallace had been born on February 21, 1962, as was I. So tomorrow would’ve been his 60th birthday as well. What’s more, Erma Bombeck was born on February 21st, as were Anaïs Nin and Jonathan Safran Foer.

I’m not saying this is anything magical. What I’m trying to demonstrate is pattern recognition. Create a pattern, then allow your reader to determine its meaning. Personally, I was thrilled to find I shared a birthday with so many writers. And that my name had been linked with that of Foster Wallace. But in hindsight, it doesn’t mean anything.

Now one last thing …

A Note to the Chuck of the past, “I wish you hadn’t worried so much. You had more potential than you gave yourself credit for. Thank you for not dying.”

How did I get from sixteen to sixty so fast?

I think. I might have the museum wrong. Correct me if you know otherwise.

It’s amazing how little use it got over the past 40+ years, and recently I gave it to Goodwill. Who has time to polish silver?

To my teacher and good friend— may you have a spectacular birthday and be proud of how far your life/work has gone forth. May small things, like the colored glass, the rocks you built the castle with, your dogs (past and present) bring you such happiness that you have to squint to shy a tear away. You came so far! You’re still doing it!! There are books you have written that are still to be discovered by further generations. That’s one helluvah legacy! Then, there’s all of us— beyond happy to learn from your life and continuous kindness. May 60 be good to you and keep pushing you to be more than who you were yesterday. Thank you for sharing your life with so many of us. Lots of love and shorter sentences!

(Also, I’m a huge Imogen Cunningham fan—- my photos in college were often compared to her work—- I would have passed out sitting across from her well-known model, Twinka!!! Omg. I also have a tattoo in Anaïs Nin’s handwriting on my arm)

-Kerri and Sassy. ♥️🎂🙏🏼🎁🎳🍕

Inspired. Happy birthday, Chuck!